|

PIONEERING BLACK ARCHITECTS IN NORTH CAROLINA

There were very few Black architects in North Carolina before 1970. It was tough enough for white women in a white-male-dominated profession, but for minorities it was nearly impossible. There were almost none for decades. By 1950 there were only two Black architects registered in North Carolina. By 1980 the number increased to only 65 out of a total of 1909. This series profiles the North Carolina pioneers who followed their hearts into architecture despite substantial resistance from both society and industry. There are still relatively few Black architects practicing in North Carolina. There are no women on this list because there were no female Black architects before 1970. It was not until 1990 that Danita Brown became the first Black woman licensed to practice architecture in North Carolina. She was one of the first thirty in the entire United States. Many thanks to Mechanics and Farmers Bank; The Michael Okoli Agency; Arthur Clement; The Freelon Group; Cheryl Walker; and Gantt Huberman Architects for research support. HENRY BEARD DELANY (1858-1928)

Born in Georgia of enslaved parents, Delany grew up in Fernandina FL where he went to school and learned brick laying and plastering trades from his father. In 1881 Delany entered Saint Augustine's School in Raleigh to study theology. After graduating in 1885, he joined the faculty, remaining there until 1908. He married Nannie James Logan of Danville, Virginia, another St. Augustine's faculty member, who taught home economics and domestic science. The couple had ten children including Sarah Louise and Annie Elizabeth who became famous with their 1993 joint autobiography Having Our Say: The Delany Sisters' First 100 Years. Delany joined Raleigh's Ambrose Episcopal Church, and in June 1889 was ordained a deacon. Three years later he was ordained as a priest. He steadily rose in the Episcopal Church hierarchy, becoming Archdeacon in 1908 and Bishop in 1918. He was a tireless organizer for Black education, setting up schools across the state. Because of his education work, Shaw University in Raleigh awarded Delany an honorary doctor of divinity degree in 1911. Although not formally trained as an architect, Delany helped in the design of Saint Agnes Hospital on St. Augustine's campus in 1909. This hospital was, through the 1940s, the only Black-owned hospital in North Carolina and the only hospital open to Black people in eastern North Carolina. The boxer Jack Johnson died at Saint Agnes in 1946 after an automobile accident. Although not the main designer, Delany was the on-site architect and construction supervisor. Adapted from BlackPast; African-American Architects: a Biographical Dictionary, 1865-1945. JOHN MERRICK (1859-1919)

Merrick was born enslaved in Clinton NC. His white father, the plantation owner's son, disavowed any responsibility for John, his brother Richard, or his mother Margaret. In 1871 Margaret Merrick left the plantation and moved her family to Chapel Hill to work as a domestic while John worked in the local brickyard and went to school. After six years in Chapel Hill, the family moved to Raleigh and John worked in various construction jobs including the first large buildings at Shaw University. When construction became hard to get, he worked shining shoes in a Black barbershop and eventually learned barbering. In 1880 Merrick married Martha Hunter of Raleigh and they had five children. He became the favorite barber of Durham industrialist Washington Duke who traveled to Raleigh because of the poor-looking haircuts he got in Durham. Duke persuaded Merrick to relocate to Durham and provide the professional barbering that Duke's wealthy white colleagues wanted. Merrick opened in Durham in 1880 with a partner, John Wright, and by 1892 had as many as nine locations. Merrick began investing in real estate. The profits from his barbershops subsidized his land purchases and the construction of houses for rent. He was his own architect, drayman, foreman, and carpenter. By 1910, he owned 60 houses.

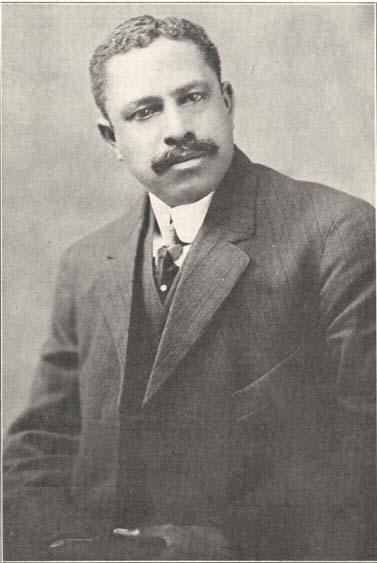

In 1898, he was one of seven founders of North Carolina Mutual and Provident Association, an insurance company. He was President until his death. Merrick, shown at left along with Dr. Aaron M. Moore and Charles C. Spaulding, built the company into the largest Black business in the nation. As the company expanded into real estate development in 1903, Merrick was North Carolina Mutual's realtor, architect, and builder. Further expanding, North Carolina Mutual established Mechanics and Farmers Bank in 1907 as a depository for customer premiums and mortgages. As many banks would not lend to minorities, Mechanics and Farmers filled an huge need in the community. In 1908, no drug stores were easily accessible to Black neighborhoods or businesses. Merrick and five other men founded the Bull City Drug Company near North Carolina Mutual and later a second store opened in Hayti. In 1910, Merrick designed and supervised the construction of a large Queen Anne-style house with a wraparound porch and polygonal tower for his family at 506 Fayetteville Street, since destroyed. Also that year, North Carolina Mutual formed a real estate subsidiary, the Merrick-Moore-Spaulding Land Company, building hundreds of low-cost rental houses across southeast Durham up until the 1940s. Merrick died in 1919. He is buried in White Rock Baptist Church cemetery in Durham. In his memory, the Liberty Ship #1990 SS John Merrick was launched into wartime service in 1943 (and scrapped in 1967). The Merrick-Moore Elementary School in Durham was dedicated in 1950. Sources include: North Carolina History Project; Spaulding Family History; African American Architects: A Biographical Dictionary, 1865-1945. WILLIAM W. SMITH (1862-1937)

Smith was born in Mecklenburg County where he lived all his life. With no formal education, Smith appeared in the Charlotte City Directory as a brick mason in the early 1890s and at the end of the decade he was briefly a partner in a brickmaking yard. By the 1900s, he had emerged as a mason, contractor, and architect — and a leader of Charlotte's Black community. In 1886 he and his wife Keziah were instrumental in founding Grace African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church. In 1902, Smith built a sanctuary for the church at 223 South Brevard Street. Smith was not the designer, but was the on-site architect. The plans were prepared by Hayden, Wheeler, and Schwend. Just down the street from the church, Smith did the masonry work for North Carolina's first public library founded for Black citizens, the Brevard Street Branch of the Charlotte Public Library (destroyed). About the same time, Smith began his association with Livingstone College in Salisbury, which was financially supported by the African Methodist Episcopal Zion denomination. In 1906 Smith designed and built Hood Hall. It is believed that Smith was the architect for the renovations to Ballard Hall, which was damaged in a 1905 storm. Smith was also the architect and contractor for Goler Hall, the college's largest building, a women's dormitory with ninety sleeping rooms, a dining room, post office, and staff quarters.

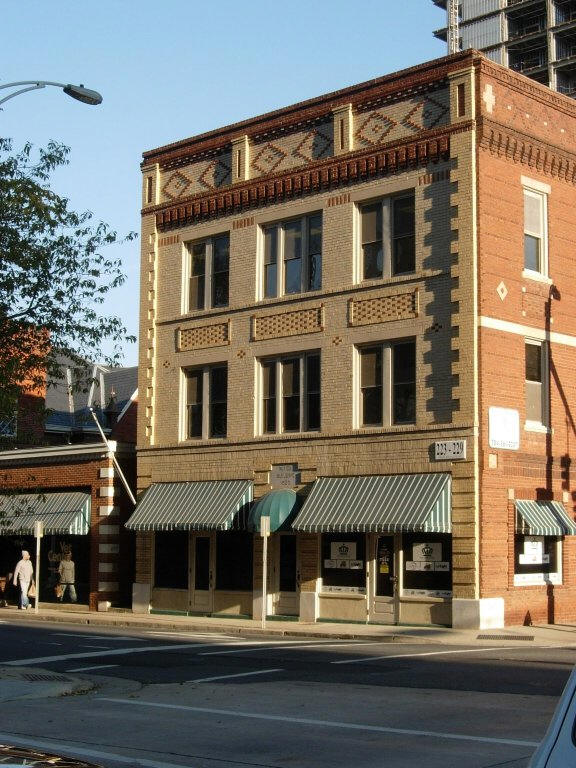

The best example of Smith's design work in Charlotte is the 1922 Mecklenburg Investment Company Building, left, on South Brevard at 3rd Street. The building was funded by a group of Black professionals who wanted to rent office space downtown, but were denied by white building owners due to race. The ground floor held shops, the second floor held offices flanking a central corridor, and the third floor held a doctor's office and a large lodge hall with a coffered wooden ceiling. Two other commercial buildings that stood near the Mecklenburg Investment Company Building were the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Publishing House (1911) and the Afro-American Mutual Insurance Company building (1911). Both buildings were two stories tall with massing and lively polychrome that stamped them as Smith designs. They were demolished during the city's urban renewal activities. Smith is buried in a mausoleum he designed in Charlotte's Pinewood Cemetery. Adapted from NC Architects and Builders; African American Architects: A Biographical Dictionary, 1865-1945. ROBERT ROBINSON TAYLOR (1868-1942)

The first professionally trained Black architect in the United States was Robert Robinson Taylor, a native of Wilmington NC. The Taylor family resided at 112 North 8th Street (destroyed) and Taylor went to high school at the abolitionist American Missionary Association's Gregory Institute in Wilmington. Taylor was the first Black architecture student at MIT, graduating in 1892. From 1899-1902 Taylor worked on his own and for the architectural firm of Charles W. Hopkinson in Cleveland OH. He spent most of his career teaching and designing the buildings on Tuskegee University's campus, including the original Tuskegee Chapel erected between 1895 and 1898 and The Oaks, built in 1899, home of the Tuskegee University president. In North Carolina, Taylor designed the Carnegie Library in 1906 on Livingstone College's campus in Salisbury. He retired in 1933 and returned to Wilmington. He was appointed by the Governor of North Carolina to the Board of Trustees of what is now Fayetteville State University. He died in 1942 attending services in the Tuskegee Chapel. Robert Rochon Taylor, his son, became an architect in Chicago. His granddaughter is Valerie Jarrett who became a senior advisor to President Barack Obama. GASTON ALONZO EDWARDS (1875-1943)

Gaston Alonzo Edwards was the first Black architect licensed in North Carolina and the only registered Black architect in the state for many years. According to his granddaughter and biographer, Hazel Edwards, he was born in Belvoir, Chatham County, North Carolina, one of six children of Mary Edwards, a Black woman, and William Gaston Snipes, a white farmer. His parents were forced to live as neighbors; state law at the time forbade marriage between races. When he was 21, Edwards entered what is now North Carolina A&T University in Greensboro, graduating in architecture in 1901. After graduation Edwards took coursework at Cornell. Edwards moved to Raleigh around the turn of the century where he established the mechanical department at the state school for the Deaf, Dumb, and Blind for Black students. Soon after this he joined the faculty at Shaw University to teach and later responsible for the University's building program. His Raleigh buildings include Shaw's Tyler Hall (then the Leonard Medical School Hospital); and the Masonic Building on South Blount Street. In 1909, Edwards married Catherine Ruth Norris, a music student at Shaw, and they had five children. In 1917 the family moved to Kittrell NC where Edwards became president of Kittrell College. Edwards attained considerable recognition in the state. In 1912 he was appointed by the Governor of North Carolina as a delegate for the Negro National Educational Congress. When licensure became mandatory for North Carolina architects in 1915, he became the state's first registered Black architect and was the only one for over 30 years.

In 1929, the family moved to Durham and Edwards ran a small design practice. His wife founded and was the first chairman of NCCU's Music Department. With the onset of the Depression, Edwards re-entered educational employment as principal of the Lyon Park Elementary School and the Whitted Junior High School (later Hillside High School), while continuing to design houses. He was prominent in Durham as a board member of Mechanics and Farmers Bank, Bankers Fire Insurance Company, and what is now the Durham Committee on the Affairs of Black People.The family resided in a house at 1712 Fayetteville Street, left, now part of the NCCU campus. Both the Edwards are buried in Mount Hope Cemetery in Raleigh along with several of their children. Adapted from NC Architects and Builders; African American Architects: A Biographical Dictionary, 1865-1945. WILLIAM HENRY PITTMAN (1875-1958)

Pittman was born in Montgomery AL. In 1892, he enrolled at Tuskegee Institute, finishing in mechanical and architectural drawing in 1897. With financial support from Tuskegee's, Booker T. Washington, Pittman continued his education at Drexel Institute in Philadelphia with a diploma in architectural drawing in 1900. Returning to Tuskegee Institute as assistant in the Division of Architectural and Mechanical Drawing, he supplied blueprints for several buildings on the Tuskegee campus. In May 1905 Pittman left Tuskegee for Washington DC as a draftsman in the office of John Anderson Lankford. Within a year he opened his own office. In the fall of 1906, he entered and won the competition for the design of the Negro Building at the 300th Anniversary Jamestown VA Exposition, the first known federal contract with a Black architect. In 1907 Pittman married Portia Marshall Washington, daughter of Booker T. Washington. She was a professional pianist who had been educated in Europe and taught music. During these years in DC, Pittman designed several schools and a notable YMCA whose cornerstone was placed in November 1908 by President Theodore Roosevelt. His practice expanded to NC and TX, and the family moved to Dallas in 1912. As Dallas' first Black architect, he was initially the toast of the town, gaining a commission for the Knights of Pythias building, an important Black social center. By the 1920s, however, Pittman was unable to get design work. He was demanding, eccentric, and ultimately unpopular. The descent of his brief architecture career was accelerated by a combination of arrogance and personal frustration. Few whites used his services, and that Blacks who could afford his services usually took their business to white architects. A large part of Pittman's problem may have been his light-colored skin, said Donald Payton, associate researcher for the Dallas Historical Society who helped raise funds to mark Pittman's unmarked grave in 1985. "The guy looked as white as any white man, yet he was very into issues of race. He suffered the plight fair-skinned Blacks have always suffered. He was too white to be accepted by Blacks and too Black to be accepted by whites." The Pittmans separated in 1928 and Portia moved back to Tuskegee. In 1931, Pittman turned to publishing to campaign against the hypocrisy of Black leaders. He published "Brotherhood Eyes" every Saturday, gathering gossip sent in by correspondents called "the Eyes" across the South. His constant criticisms both enraged and enthralled the community. There were unsuccessful local efforts to get rid of Pittman on grounds of libel. Ultimately, however, he was convicted for sending obscene material through the mail. He served two years of a five year sentence at Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary in Kansas. Portia Pittman helped get him released early through her friendship with Franklin D. Roosevelt's housekeeper. Pittman remained in Dallas until his death in 1958 working primarily as a carpenter. He left a legacy of significant buildings. In Durham, he designed Avery Auditorium, the Central Dining Hall, a dormitory, the Theology Hall, and the President's House at what is now NC Central University. He also designed the 1910 White Rock Baptist Church at 3400 Fayetteville Street in Durham. Video on Pittman's early career. Sources include: Dallas Times Herald, 12/7/1986; The Pride of Sidney Pittman by Mary Barrineau; Portia: The Life of Portia Washington Pittman by Ruth Ann Stewart; African American Architects: A Biographical Dictionary, 1865-1945. CALVIN ESAU LIGHTNER (1877-1960)

Lightner was a native of Winsboro SC. In 1881 the family migrated to North Carolina. After high school, he played on Shaw University's first football team in 1906, graduating the following year. By 1909 he completed embalming school in Nashville TN and returned to Raleigh to become the city's first licensed Black mortician. Lightner was also an architect. Without a formal education, Lightner designed and constructed his 1907 Raleigh home at 419 South East Street (destroyed), a modified Triple A Craftsman. By 1911 he founded the Lightner Funeral Home, which remains in the family to this day. He also designed and constructed commercial Raleigh buildings on East Hargett Street. He also designed the second version of the Davie Street Presbyterian Church. In 1919 Lightner designed and built the Lightner Building in the 100 block of East Hargett Street. The mixed-use building contained dental and medical offices, apartments, beauty salons, a barber shop, and a tailoring and dry cleaning business.

Encouraged by that success, he completed the Lightner Arcade and Hotel in 1921 (left photo) in the same block of Hargett Street. The arcade also contained dental and medical offices, a barber shop, a drugstore, the first home of The Carolinian (an amusement emporium), Harris Barber College, a haberdashery, a store, a ballroom, and the first Black hotel in the state of North Carolina. The Lightner Arcade and Hotel became the social hub of Black society and hosted Duke Ellington, Count Basie, and other big bands. Lightner designed many houses and buildings in southeast Raleigh including the Capehart House (destroyed). In Durham he designed the first headquarters for the NC Mutual Life Insurance company at 114 Parrish Street (right photo) in 1922. Lightner's son, Clarence Lightner, became a business, civil rights, and community leader. He was elected to the Raleigh City Council from 1967 to 1973 and later became Raleigh's first Black mayor. In 2003 Raleigh announced it would name a new 17-story, 305,000 sf Law Enforcement Center in his honor. Adapted from: African American Architects: A Biographical Dictionary, 1865-1945. JULIAN FRANCIS ABELE, AIA (1881-1950)

Abele was one of the most prolific architects in America between 1890 and 1920. He was the eighth of eleven siblings. In 1893 he enrolled at Philadelphia's Institute for Colored Youth (ICY), founded by the Quakers. In June 1897 Abele graduated and enrolled in the Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Arts, graduating in 1898 with a Certificate in Architectural Design, the first Black graduate at that school. In the fall of 1898 Abele was accepted into the University of Pennsylvania School of Architecture and in 1902 became the first Black graduate and only the second in America to earn a degree in architecture, following Robert Robinson Taylor (profile above). Abele went on to graduate from the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in 1903. By 1906, he was working for Horace Trumbauer transforming the extravagant demands of his Philadelphia, Manhattan, and Newport clients into huge mansions, glamarous hotels, and awe-inspiring public libraries. By 1908 Abele was senior designer responsible for the look of all major buildings. Abele spent his entire 44-year career with the Trumbauer firm. He designed over 200 buildings.

Abele married white Paris émigré musician Marguerite Bulle in 1925. Their marriage unravelled when she had an affair with another musician. Julian Abele kept the children but did not remarry. He was known in the community as a staunch Republican, religious but not a church-goer. James Duke, president of both the American Tobacco Company and Southern Power Company, was one of Trumbauer's top patrons. Abele designed Duke's eighteenth-century 5th Avenue townhouse in 1909. Abele was Duke's master architect for eleven Georgian-style and thirty-eight Collegiate Gothic-style buildings for the Duke University from 1925 to 1940, including the Chapel and the basketball arena. According to legend, Abele never set foot on Duke University's campus to avoid the dehumanizing Jim Crow laws in North Carolina. Plus, Duke remained a whites-only institution until 1961. However, Susan Tifft reported in 2005 that Abele's remote administration of Duke may have not been true. "In the early 1960s, John H. Wheeler, a prominent Black banker in Durham told George Esser, then executive director of the North Carolina Fund, that he recalled Abele coming to visit the campus during construction. What's more, in a 1989 interview, Henry Magaziner, son of Abele's friend and Penn classmate Louis Magaziner, recalled Abele telling him that a Durham hotel had refused to give him a room during a trip to the University, while accommodating his white associate, William Frank. Abele died alone in his Philadelphia row house after suffering a heart attack. His son Julian Abele Jr., and his nephew Julian Abele Cook both became architects. Julian Abele Cook studied architecture at Penn with the Class of 1927; two of his grandchildren have continued the family tradition, Susan Cook as an architectural engineer and Peter Cook as an architect. It was Susan Cook, while a student at Duke University during the 1986 student protests against apartheid in South Africa, who wrote the letter to the student newspaper which made public Julian Abele's role in the creation of the Duke campus. Sources: African American Architects: A Biographical Dictionary, 1865-1945; Penn Archives; Free Library of Philadelphia; Duke Archives.

JOHN AYCOCKS MOORE (1888-1939) Moore was born in Rock Hill NC near Wilmington. Moore's father was a farm worker and his mother was a homemaker. There is no data on how Moore escaped the farming life to become an architect or where he received his education. By 1911 Moore was in Washington DC working for one year as a draftsman for the Supervising Architect's Office in the US Treasury. Beginning in 1912, Moore listed himself as an architect in Boyd's Directory of the District of Columbia and had a private practice until 1917. Moore designed a laundry and model home, and constructed several complicated carpentry projects for the National Training School for Women and Girls. Don Speed Smith Goodloe, the first principal of what is now Bowie State University commissioned Moore to design his 1915 house, which still stands northwest of the campus. From 1918 to 1919 he was in the Army with the 28th Construction Company Air Services Aeronautics stationed at Langley Field in Virginia. His honorable discharge states that he was thirty years of age when he joined and his occupation was a carpenter. In Washington, he stopped advertising himself as an architect.

In 1920, Moore married Susan Brown. Her father, William A. Brown, was the proprietor of the Plaza, a popular Black restaurant in Wilmington. Shortly after the wedding, he left Washington and they moved in with his in-laws. They lived at 19 South 12th Street in Wilmington, left, until his death. From 1922-1938, he is listed variously as an architect, contractor, carpenter, and recreation worker. Working with brother Joshua, who was also a carpenter, he is credited with designing and building the 1929 Dr. Frank W. Avant house at either 710 or 813 Red Cross Street. Avant was the first Black physician to practice in the state of North Carolina. According to oral family history, the Moore brothers were responsible for the design and construction of many houses in Wilmington's Forest Hills neighborhood. Poor health was perhaps the reason that Moore took an indoor job at the County Recreation Office because he died the next year in Columbia SC. Adapted from: African American Architects: A Biographical Dictionary, 1865-1945.

HILYARD ROBERT ROBINSON (1899-1986) A native Washingtonian, Robinson graduated in 1916 from the M Street High School. He studied at the Philadelphia School of Industrial Arts, leaving in 1917. From there he went into the Army, serving in France during WWI. Robinson was in Paris for the Armistice and was so profoundly impressed by the architecture that upon returning home in 1919 he transferred to the architecture program at the University of Pennsylvania. During the summers of 1921 and 1922, while working as a draftsman for Vertner Woodson Tandy in Harlem, Robinson met Paul B. LaVelle, a friend of Tandy's and practicing architect and Professor of Architecture at Columbia University. LaVelle assisted Robinson's transfer to Columbia in 1922 and employed him as an architectural draftsman from 1922 to 1924. Prior to receiving his BA in Architecture from Columbia in 1924, Robinson began a long relationship with Howard University teaching at its new School of Architecture. Subsequently, Robinson served as instructor an Chair until 1937. He also designed eleven Howard buildings that helped establish a distinct Modernist feel to the campus.

Robinson's significant buildings include the Langston Terrace Dwellings, left, built with architect Paul Williams in 1936 and considered the first public Black housing project. He drew a number of residences for fellow faculty at Howard University, including the Nobel Peace Prize winner Ralph Bunche and Rayford Logan. Both residences are located in the Brookland neighborhood of Washington DC. Another highly significant project was the Tuskegee Army Air Field, the first defense contract given to a Black person. When Robinson received his MA in 1931, he and his new white wife, Helena Rooks Robinson, embarked on an eighteen-month leave of absence touring Europe as a Kinne Fellow. From Berlin, Robinson attended the Ausland Institute and traveled extensively to examine and photograph post-WWI construction techniques and government-sponsored housing solutions. He went frequently to Paris and toured the 1931 exposition. Robinson returned home to Washington with a comprehensive understanding of housing solutions and resumed teaching at Howard University in 1932. His desire to apply European low-cost housing efforts to the benefit of Black Americans led to a second leave of absence from Howard University and employment by the Public Works Administration in 1935 as chief architect. He served on the National Capital Planning Commission from 1950 to 1955 and was director of the Washington Housing Association. He was one of DC's most prolific and successful Black architects of the first half of the twentieth century. In North Carolina, he designed the Student Union, Harris Dormitory, Moore Faculty House, and Varrick Auditorium for Livingstone College in Salisbury. Adapted from: African American Architects: A Biographical Dictionary, 1865-1945; Wikipedia.

DEWITT SANFORD DYKES, AIA (1903-1991) Dykes was born in Gadsden AL. Around 1911, the Dykes family relocated to Newport TN where DeWitt went to school and became a brick mason by age fourteen. His interest in masonry led to a desire to become an architect. His father was skeptical that his son could earn a living as an architect because of racial discrimination by white individuals and institutions and the undependable support of Black individuals and institutions. Dykes instead chose the ministry as a profession. From 1919 to 1926, Dykes studied in the pre-college division of Morristown Normal & Industrial College in Morristown TN. He then entered Clark University in Atlanta, receiving an artrius bachelor's degree in 1930. During his junior and senior years at Clark University, Dykes studied at Gammon Theological Seminary in Atlanta, from which he received a Bachelor of Divinity degree in 1931. On a scholarship, Dykes entered the graduate program at Boston University School of Theology and earned a sacred theology Masters in 1932. While he was studying to become a minister, Dykes earned money as a brick mason. From 1932 to 1954, Dykes was the pastor of churches in the East Tennessee Annual Conference of the Methodist church. Starting in 1954, Dykes worked as an administrator for the United Methodist denomination. He became a staff member of the Division of Missions from 1956 to 1968. Dykes was responsible for determining the financial feasibility of constructing Methodist churches, evaluating building sites, analyzing Building and Zoning Codes, performing design reviews, supervising construction, and administering payment draws. Because Dykes was not registered, Dykes submitted floor plans that he had prepared to the director of the Department of Architecture, Norman G. Byar, who was a licensed architect in the Philadelphia office of the Division of Missions. During his years with the Division of Missions, Dykes designed seventy-two Methodist churches and other religious buildings, as well as a community fire hall in Frakes, Kentucky. Independent of the Methodist church, Dykes designed six churches under the license of Knoxville engineer Milo C. Fear. In 1960 Dykes took courses in architecture from the International Correspondence School of Scranton, Pennsylvania, and received a certificate of completion in 1965. In 1968 Dykes took the oral part of the examination to become a registered architect. A year later, he passed the written portion and became a registered architect in the state of Tennessee in 1970. That same year he was accepted into the AIA. Dykes practiced from a home office on Dandridge Avenue in Knoxville from 1970 to 1976. He moved his practice to several office buildings from 1976 to 1986, occasionally apprenticing architectural students from the University of Tennessee. He designed dozens of mostly religious buildings all over the south, including three in Greensboro: Bass Chapel Methodist Church Education Building (destroyed); Laughlin Memorial Methodist Church; and the Mount Tabor Methodist Church Education Building. Adapted from: African American Architects: A Biographical Dictionary, 1865-1945; Historic Parrish Street.

TAFT H. BROOME (1908-1989) Broome earned a BS degree in Architecture in 1929 from NC A&T University in Greensboro. He was principal the next two years at Catawba High School in Catawba. He served the next nine years as principal of Central High School in Newton. He earned Masters of Arts in Education from University of Michigan in 1943. Broome was principal of Ridgeview High School in Hickory from 1944 until promotion to the school system assistant superintendent in 1968. Part of his responsibilities included supervising design. To save the school system money, he often did the school design himself and got the architects of record to sign off on it. He also designed three churches in Hickory, plus his own 1951 house at 215 8th Avenue Drive SW, which included innovations in the overhangs and the wall structure. The unique house drew instant attention. People came in off the highway thinking it was a Hickory welcome center! It was purchased from his son, Taft Broome Jr., and has since been renovated as part of a HUD grant. In 1972, Broome was the first Black man to receive an honorary degree from Lenoir Rhyne College. Not long after, a park was named for him in Hickory.

HENRY LEWIS (ACE) LIVAS (1912-1979) Livas was born in Hot Springs AR. In 1916 his father moved the family to Springfield OH and he attended Woodward Elementary until 1922. His mother died when he was in second grade and his father remarried his piano teacher. The family then moved to Paris KY where Henry attended Western Junior High School, graduated in 1929. In 1935 he graduated from Hampton Institute with a BS degree. From 1936 to 1937, Livas was employed by Berry Construction Company in Durham NC, working on a housing project. He married Cocheeys Smith of Durham in 1940 and they had one son, Henry Jr. From 1937 to 1941, Livas taught at Arkansas Mechanical & Normal College in Pine Bluff AK and was superintendent of buildings and grounds. From 1942 to 1943, he was a civilian teacher at the U.S. Army Engineering School affiliated with Virginia State College in Ettrick. In July 1944, he was enrolled at the Pennsylvania State College School of Engineering, where he earned an MS in architectural engineering with a minor in Architecture. His thesis topic was "Building Code Requirements for Structures Housing Selected Mixed Occupancies," which played to his engineering strengths instead of architectural design. Livas returned to Hampton in 1945 as a newly minted associate professor and taught for seven years. He was active in campus life as well, starting a choir. In 1952 he opened Livas & Associates in Hampton VA and simultaneously in Burgaw NC where he maintained a second home. Rejected by the Virginia AIA in 1950 due to race, he applied and was accepted in by the AIA of Washington DC. He was licensed in NC, VA, MO, and DC. His office has been in business for 55+ years as the Livas Group in Norfolk VA. Adapted from: African American Architects: A Biographical Dictionary, 1865-1945.

JASMINIUS (J. W. R.) WILSONI RUDOLPHUS GRANDY III (1919-2001) Grandy was born in Windsor NC in a family with 16 brothers and sisters. They raised cotton, corn, soybeans, and a garden grown from seeds purchased mail-order from Sears. Encouraged by his father and mother, J.W.R. would later expand on his agricultural upbringing to study horticulture and landscape architecture. After his father died, Grandy graduated from the public schools of Bertie County and went on to attend NC A&T University, earning a BS in Horticulture in 1940. He and a few classmates opened the first Black-owned floral shop in Greensboro around 1939. Grandy pursued graduate school in landscape architecture at Cornell University between 1940 and 1942 while working as a chef for several white-only fraternities on campus. Before graduating, he had to return home to save the family farm, threatened with foreclosure. He was successful and kept the farm in the family for another generation. With an interest in teaching, Grandy obtained a faculty position at Southern University School of Architecture in Baton Rouge LA teaching horticulture. After a year, he returned to teach at NC A&T and taught horticulture and landscape architecture design until his retirement forty-two years later. By 1975 Grandy had become Superintendent of Grounds at NC A&T University. He led the University to become the first Black campus to earn accreditation for its undergraduate program in landscape architecture. Grandy was the landscape archtiect for the Kenneth Lee House designed by Blue Jenkins. Adapted from African-American Architects: a Biographical Dictionary, 1865-1945.

FLOYD A. MAYFIELD (1898-1975) Mayfield grew up in Lake Providence LA. He graduated from Howard University with post-grad work at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. In 1930, Mayfield was head of the Contracting and Building Department of NC A&T in the College of Architecture and Engineering. In 1941, he headed the Department of Architecture, where he stayed until 1947 and went into private practice. He was one of the first Black candidates for Greensboro City Council. His buildings include the Skating Rink on West Lee Street, the Maurice Lytell House on Benbow Road (photo below), and the York Home on Young Estate.

GERARD E. GRAY, AIA (1919-2001) Gray was born in Cheraw SC and graduated from A&T in 1942 with honors. He served in the US Army during WWII as a commissioned officer in the Army Corps of Engineers. His unit saw action in Africa, Europe, and the South Pacific and later participated in the liberation of the Philippine Islands. Mr. Gray also served in the Army Corps during the Korean War. He received his Master's Degree in Architectural Engineering from the University of Illinois and conducted post-graduate studies at Penn State, the Universities of Illinois and Colorado, Michigan Tech and the US Navy Civil Engineering School. His professional career included serving as Associate Professor and Full Professor of Architectural Engineering at NC A&T from 1942 to 1974. He also worked occasionally with Blue Jenkins on projects. From 1974 to 1981, he served as Director of NC A&T's Physical Plant. In 1982, he left to serve as VP and Director of Physical Plant at Prairie View A&M where he retired in 1984. Upon retirement, Gray moved to Philadelphia, where he died in 2001. There is an endowed scholarship in his name at NC A&T. More on Gray's houses. Sources include: 1970 AIA Directory; NC A&T University Ayantee Yearbook; Major Sanders.

WILLIAM ALFRED STREAT JR., AIA (1920-1994) Streat was born in Clover VA and spent his childhood on the campus of Saint Paul's College in Lawrenceville VA where his parents William A. Streat Sr. and Marie Green Streat were faculty. Streat completed Saint Paul's high school in 1937 and received a BS in Building from what is now Hampton University in 1941. During World War II, Streat served in the U.S. Corps of Engineers and in the Army Air Corps with the 99th U.S. Pursuit Squadron, the legendary Tuskegee Airmen. He earned a BS in Architecture from the University of Illinois in 1948 and an MS in Architectural Engineering from MIT in 1949. Streat completed additional study in civil engineering at Duke University, the University of California at Berkeley; architectural criticism at Harvard University/MIT, and city and regional planning at Columbia University. From 1950 to 1952, he was Structural Consultant for Edward Loewenstein in Greensboro. In 1951, Streat married Louise Guenveur of Charleston SC who was professor and chair of the Department of Home Economics at Bennett College in Greensboro. In 1952 he became the second Black architect licensed to practice in North Carolina (Gaston Alonzo Edwards was the first). Streat spent the summer of 1957 at Columbia University in City Planning and Architectural History. He travelled extensively, with visits to Mexico City in 1958 and Portugal, Gibraltar, Spain, Italy, Switzerland, Germany, France, England in 1967. Streat had a long career in academia. He was Professor and Chair of the Architectural Engineering Department at NCA&T University in Greensboro from 1949 until retirement. The department grew from twenty students to 200 under his leadership and included a tenfold increase in faculty and the addition of a master's degree program in architectural engineering. He applied for membership in the all-white AIA North Carolina in 1961 and was accepted, although not without protest from several white members. After retirement from teaching in 1985, he continued a limited architectural practice and became actively involved with his wife as a benefactor to the United Negro College Fund, Saint Paul's College, Hampton University, and NCA&T. Since her husband's death, Louise Streat endowed scholarships in his name at NCA&T, Saint Paul's College, and Bennett College. More on Streat's houses. Adapted from African American Architects: A Biographical Dictionary, 1865-1945; CRS Archives.

WILLIE EDWARD (BLUE) JENKINS (1923-1988) Jenkins was born in Raleigh. He graduated from Washington High School and served in the Army Corps of Engineers from 1943 to 1946. He married Gladys Rand in 1945 and they had one daughter, Miltrine. Following the Army, he entered NC A&T University and earned a BS degree in architectural engineering with high honors in 1949. That year, Edward Loewenstein hired Jenkins as his firm's first Black architect. In 1953, Jenkins was the third Black architect to be registered in North Carolina. Under Loewenstein, among many other projects, Jenkins served as design architect for the Dudley High School gymnasium in Greensboro, innovative because of its intersecting roof arches and many windows. In 1962 Jenkins left Loewenstein and opened his own practice with many projects at NC A&T, including the football stadium and the Ronald McNair School of Engineering (with J. Hyatt Hammond Associates). He also designed the NCCU Law School Building. In 1972 he received the Outstanding Achievement Award from the NC A&T School of Engineering. In 1975 Jenkins was appointed to the North Carolina Board of Architecture. More on Jenkins and his houses. Adapted from: African American Architects: A Biographical Dictionary, 1865-1945.

WILLIAM GUPPLE (1923-2002) As a boy, Gupple drew constantly and always dreamed of becoming an architect. He graduated from NC A&T University and was hired by Edward Loewenstein, a white architect in Greensboro. This made Gupple the second Black architect to be hired by a white firm. Blue Jenkins, who also was hired by Loewenstein, was the first. Gupple worked there until leaving for New York City in the early 1960s. For the next 37 years, he worked for several design firms plus American Home Products. He moved back to Greensboro in 1997 and retired.

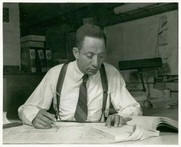

WILLIEX (WILL) EMMANUEL MERRITT JR. (1928-2008) Merritt was born in Elizabeth City NC. He served in the Army during WWII as a First Lieutenant. Upon release he earned a degree in architecture from Hampton University in 1949. He worked for Edward Loewenstein in Greensboro for a few years, then when that firm's work slowed he assisted Voorhees and Everhart in High Point. This is according to Ruth Summey who worked with Merritt at the latter firm. The photo is from a Voorhees and Everhart office picture in 1954. After a few years on his own in High Point, Merritt left for Michigan. Merritt was the first Black architect in Lansing MI. He worked for the City of Lansing and the State of Michigan for over fifty years. He also had a private practice called Omega Designs and was a Lector and Eucharistic Minister at Holy Cross Catholic Church.

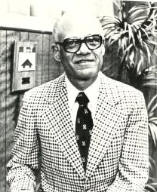

CLINTON EUGENE GRAVELY, AIA (1935-) Gravely grew up in Reidsville NC where his father and grandfather were contractors. Frequently they got design requests and during high school, Gravely drew up simple plans which the company would then build. In 1955, he entered Architecture at Howard University, finishing in 1959. After eight months in the military he returned to NC and worked for his father until a position came open with the Greensboro architecture firm Loewenstein Atkinson. They were the most progressive in the state for hiring minorities. When Gravely joined, Edward Loewenstein already had two Black architects, Willie Edward Jenkins and William Gupple. Gravely took Gupple's position when the latter left for New York in 1961. Gravely recalls, "The AIA was very supportive of Black architects. However, there was a white group called Greensboro Registered Architects and they did not want Black members." Eventually the group admitted him and a few years later it disbanded. Gravely opened his own firm in 1967 and over the years amassed a portfolio of over 800 projects, including 100 churches and the NC A&T Library. He was the original architect for Greensboro's International Civil Rights Museum which was completed by the Freelon Group. He continues in practice in Greensboro. More on Gravely and his houses.

MAJOR SPENCER SANDERS JR., AIA (1943-) Sanders was born in Concord NC. He started studying Architectural Engineering at NC A&T University in 1961 and worked as a bottle inspector for Sundrop while in school. Later, he worked for Blue Jenkins starting in 1966, starting a long association with the firm. Contrary to some accounts, he never worked for Ed Loewenstein. Graduating from NC A&T in 1971, he continued to work for Jenkins through 1978. He moved to Wisconsin and worked for American Medical Buildings from 1978 to 1980 and for Shephard Legan Aldrian from 1980 to 1982 before again returning to Jenkins' firm from 1982 to 1986. Sanders broke off to start his own company in 1986 which continue today. Currently he is President of Quality Housing Corporation in Greensboro, specializing in passive solar and low-cost energy solutions using SIPs - structurally insulated panels, a continuous core of energy-efficient rigid foam insulation laminated between two layers of structural board. More on Sanders and his houses.

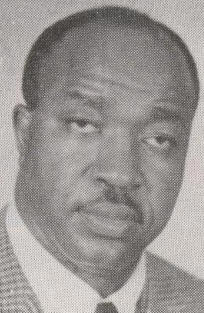

HARVEY BERNARD GANTT, FAIA (1943-) Gantt grew up in Charleston SC, graduating from Burke High School second in his class. His father was a carpenter, plus an early talent for drawing led to Gantt's choice of a career in architecture. After attending Iowa State University 1960-1962, he was repeatedly denied admission into Clemson University's Architecture program. After exhausting all administrative channels, he took Clemson to court on charges of discrimination and won, gaining admission and graduating in 1965. From 1965 to 1968, he interned at Odell in Charlotte, the first Black architect the firm had ever hired. He graduated in 1970 from MIT with a master's degree in architecture and became founding partner of Gantt Huberman in Charlotte in 1971. Gantt is the most politically active architect in North Carolina history. He was on the Charlotte City Council from 1974 to 1983; the Mayor of Charlotte from 1983 to 1987; and served on the North Carolina Democratic Party Executive Council, the Democratic National Committee, and the National Capital Planning Commission. Under his leadership, the commission adopted a strategic plan for city monuments and selected sites on the National Mall for the Martin Luther King Memorial and the World War II Memorial. In 1990 and 1996, he ran unsuccessfully against incumbent North Carolina Senator Jesse Helms in two highly polarized races. Barack Obama was a volunteer for his campaign in 1996. Gantt received the AIANC Award of Excellence in Architecture in 1981 and has also received received honorary degrees from Winthrop College, Queens College, Clemson University, Johnson C. Smith University, and Belmont Abbey College. More on Gantt and his houses.

GEORGE HAROLD WILLIAMS, AIA (1943-2017) Williams grew up in Durham and went to Hillside High School. He got interested in architecture in the 9th grade and began to take drafting courses, earning a BA in architecture from Howard University in 1966. Following that was a 1968 master's degree in city and regional planning from UNC-Chapel Hill. He interned with Smith Smith Haines Lundberg Whaeler in New York City. During the summers he worked for Ray Construction in Durham on the NC Mutual Life Insurance Company building. He served as Captain in the US Air Force (1968-1972) stationed in the Philippines designing residential, educational, and military support facilities in the Far East and Europe. Upon return to the US he became architect for a new town, Soul City, in Manson NC. That position lasted three years. He moved to Gary IN working for Mayor Dick Hatchett as Director of Development and Planning for three years. Williams also had a substantial career in city management. Posts included running the Oakland Redevelopment Agency (1979-1989); Deputy City Manager for Richmond VA (1989-1991); and Durham County Manager (1991-1996). He then started a private design firm, based in Durham, consulting on architecture and economic development.

JOSEPH HENRY YONGUE, AIA (1945-) Yongue attended high school at Second Ward and graduated from NC A&T in 1969 in Architectural Engineering. During the summers he worked for Clinton Gravely. Upon graduation, he worked for IBM, entered the Army and served in Korea. At Fort Belvoir, he worked with Andrew Bryant and Vosbeck Vosbeck Kendrick and Redinger. In 1972, he returned to IBM, working under Martin Myers in the real estate and construction division. In 1975, he relocated with IBM to Research Triangle Park. By 1978, through IBM and the GI Bill, he earned an MBA in organizational behavior from Iona College. He also attended the NCSU School of Design's Graduate program. While at IBM, he ran the Design Center and led IBM to experiment with finding the most efficient office types, furniture, and configurations to accommodate the then-exploding use of desktop computers and equipment, including security areas and laboratories. He did his masters thesis on that subject. He started a private practice in 1986 and grew to several staff. By 1992, he retired from IBM and became a home inspector.

ARTHUR (ART) JOHN CLEMENT (1948-) Clement grew up in Durham near NCCU where his mother Josephine D. Clement was on the faculty. His father worked for NC Mutual Life Insurance, taught in the NCCU Business School, and was on the NCCU Board of Trustees. He is first cousin to longtime Durham City Councilman Howard Clement. A lifelong interest in architecture began when his grandfather bought him a drafting table. At age nine he created an exhibit on Frank Lloyd Wright, and in 1966 he was the first Black student accepted into the NCSU School of Design. "To say that it was a racist school (at the time) was an understatement," he recalls, although his overall college experience was positive. Clement worked for John Latimer in Durham for five summers while at NCSU and got interested in community planning and urban design, ultimately working with Henry Sanoff's Community Design Group. Clement graduated from NCSU in 1971 and went to MIT for graduate school, finishing in 1973. At that point, he served an Army deferment at Forts Bragg and Benjamin Harrison. Returning from service in 1974, Robert Burns at NCSU's School of Design recommended him to Heery and Heery in the early days of "design+," or project supervision. He worked there four years then moved to Charleston SC to work with cousin Bill Clement, also an architect. After marrying in 1980, his other cousin Mayor Maynard Jackson of Atlanta encouraged his relocation there in 1981. Jackson was pivotal in getting Black architects major commissions in the city, and Clement worked for DDR International, a construction consulting firm doing project management. In 1985, the company split and Clement went with one of the divisions, DPM. He went out on his own in 1993, joining with Delilah Wynn-Brown to form Clement & Wynn Program Managers. Sources include: Clinton Gravely; Patricia Harris; Ken Martin; Glenn Chavis; Harvey Gantt; Arthur Clement; Ruth Summey; Major Sanders; Joseph Yongue; History of the American Negro and his Institutions, Volume 4 by Arthur Bunyan Caldwell; African American Architects: A Biographical Dictionary, 1865-1945 by Dreck Spurlock Wilson; African- American Registry; Wikipedia; MIT Archives; Henry Kamphoefner dissertation by David Brook; Doris Gupple. |